Seven months of investigations. Nearly 10 hours of hearings. And yet neither Boeing nor the National Transportation Safety Board know how a 737 Max was delivered to Alaska Airlines without the four bolts needed to keep a door plug in place.

What is known: Boeing’s procedures and training – by employees, and by safety investigators – has drawn enormous skepticism and criticism from regulators. That was on full display in the first day of a two-day hearing. The NTSB called a rare public hearing to examine the near tragedy on the January 5 Alaska Air flight in which a door plug blew out, leaving a gaping hole in the side of the plane – and in Boeing’s already battered reputation.

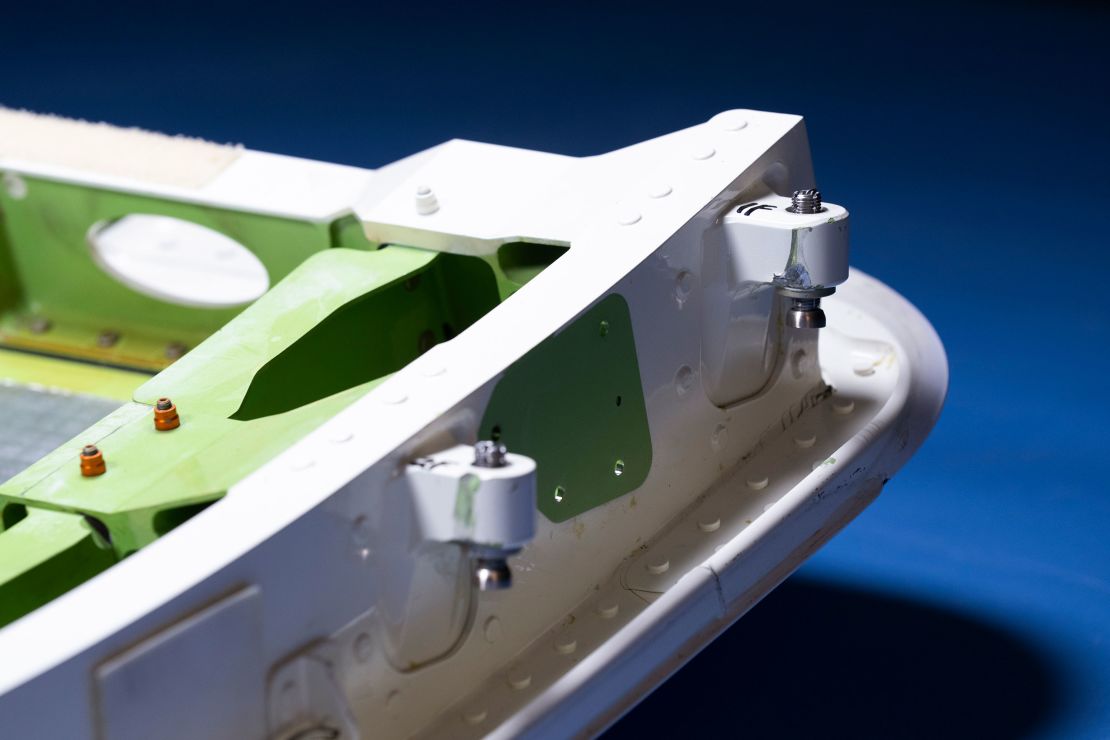

The door plug was removed at the Boeing factory in Renton, Washington, last September so that problems with some rivets could be repaired. But the necessary paperwork for that temporary door plug removal was apparently never created. So when workers replaced the door plug temporarily, other workers were unaware that bolts needed to be reinstalled, said Elizabeth Lund, senior vice president of quality for Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

But under questioning from the NTSB Lund admitted that it’s not clear who and when that door plug was put in place. That lack of information concerned members of the NTSB.

“We don’t know and neither do they and that’s a problem,” NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy told reporters during a break in the hearing.

To avoid the problem in the future, Boeing is considering adding a warning light in the cockpit that would alert pilots if the door plug moves even a little bit – well before it could blow out in the kind of accident that occurred on the Alaska Air flight.

All 737 exit doors have such an indicator light in the flight deck if one of the plane’s doors moves out of locked position. But because the door plugs are not meant to be opened and shut except as part of maintenance, the same feature is not included on them. But that change will likely take about a year to implement, and should be available to retrofit onto existing planes that have door plugs.

In the meantime, Boeing revealed it has a much more low-tech answer to ensure that planes at the factory don’t have door plugs removed and then reinstalled without the necessary bolts: The company is hanging a laminated blue and yellow tag on all door plugs when they arrive in the factory with with relatively large lettering that says “Do not open.” And in smaller font it says “without contacting quality assurance.”

Boeing employees’ testimony to NLRB regulators released as part of Tuesday’s hearings showed employees questioned the training they have to do for initiatives like reinstalling door plugs and making other changes on planes. They also complained about a relentless pressure for speed, planes hitting the assembly line floor rife with defects and employees for suppliers at Boeing factories treated like “cockroaches.”

Overall the testimony described a company in chaos with thin training and occasional confusion about who was doing what. All told the hearings so far paint a picture of a company that has yet to recover from a series of safety lapses that have left everyone from regulators to ordinary passengers rattled, lapses severe enough that the company has agreed to plead guilty to charges of defrauding the Federal Aviation Administration. Boeing faces the possibility of further criminal charges related to the Alaska Air incident. Under its announced guilty plea it will be required to operate under a federal monitor for years.

Boeing executives and those from supplier Spirit AeroSystems did their best to assure the NTSB that they have made changes in their operations that will prevent another near tragedy from occurring.

“We feel this will not be a recurring trend,” said Lund. She pointed to improved metrics and increased training and inspections that have taken place since the January 5 accident, and promised the changes at Boeing are permanent.

“These things won’t be taken away,” she said.

But she and other Boeing executives faced tough questions and criticisms from board members.

“I just want a word of caution here. This is not a PR campaign for Boeing,” Homendy said at one point in the hearing, chastising the company for focusing too much on what has happened since the accident and not enough on the problems that allowed the accident to occur.

“You can talk all about where you are today, there’s going to be plenty of time for that,” she said. “This is an investigation on what happened on January 5. Understand?”

As part of the public hearing the NTSB released 70 documents running nearly 4,000 pages, chock full of disturbing statements from Boeing workers and other experts, including from the Federal Aviation Administration, about the problems at Boeing.

Workers, many of them not identified in the transcripts released by the NTSB, spoke about being pushed to do more work than they could do without making errors, of problems on plane after plane moving along the Boeing assembly lines, with a large portion of them regularly needing to be reworked.

The problems with the planes put the workers “in uncharted waters to where… we were replacing doors like we were replacing our underwear,” one worker told NTSB investigators.

“The planes come in jacked up every day. Every day,” the worker added.

One former FAA official told investigators that he blamed problems on Boeing moving to a “lean” manufacturing model to try to cut costs, and that it cut inspections as part of that process.

“A couple of ex-Toyota managers were brought in to build airplanes the way Toyota builds cars,” said James Phoenix, a retired manager of the FAA office that oversaw Boeing. He said when the FAA demanded that Boeing restore inspections, “they complied with all of that, but slowly, very slowly.”

Phoenix told the NTSB it took two fatal crashes of the 737 Max in 2018 and 2019 for Boeing to give in to FAA demands to restore inspections it had stopped doing.

“That really didn’t change until the Max 9 accidents where it brought a lot of things to light. So you need a lot of leverage to get Boeing to change and then when Boeing changes, it’s very slow and it took a long time for them to really understand that their quality system needed to improve.”

Lund defended Boeing’s use of lean manufacturing, saying it’s not at odds with the goal of safer, better quality aircraft.

“We really believe in is the number one way to improve ‘lean’ is to improve quality,” she said.

While Lund said Boeing is committed to making further improvements, Homendy said the company had plenty of evidence of quality issues and didn’t do enough to improve its practices until the Alaska Air incident.

“Where are we going in the future? So we don’t end up in another situation… (where further change comes from) a reaction to a terrible tragedy,” she said.

CNN’s Owen Dahlkamp, Danya Gainor, Celina Tebor, Nicki Brown, Ramishah Maruf and Samantha Delouya contributed to this report.